Auf die Plätze ... lernt, taucht, schützt!, Senegal

Darum geht's?

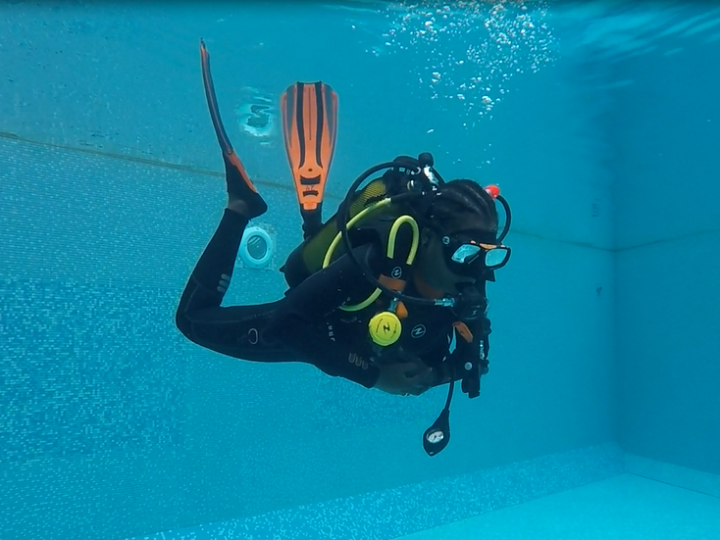

Es geht um einen Tauchkurs als Ergänzung der theoretischen Ausbildung junger afrikanischer Schützer der Meeresökosysteme Westafrikas, der künftigen grünen Champions.

Lernen ist gut, anwenden ist besser!

Studierende in Westafrika haben leider nur allzu selten die Möglichkeit, das, aus ihren Büchern und Vorlesungen bekannte, in der Realität zu sehen, zu entdecken und auszuprobieren.

Stellt Euch vor, Ihr würdet eine Sprache lernen, die ihr nie anwendet, oder ein Instrument lernen, das ihr nie spielt! Kaum vorstellbar!

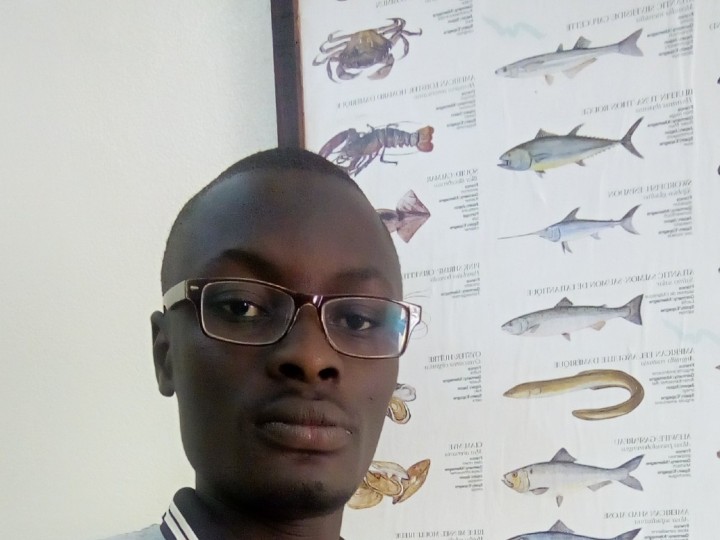

Dies ist umso unvorstellbarer, wenn es um den Schutz der Meeresökosysteme geht, ohne jemals darin einzutauchen! Deshalb wünschen sich Aliou Ngom und Amadou Sene, zwei Studenten des Masters für „Meeresbiologie und Meeresökonomie“ am Institut Universitaire de Pêche et d’Aquaculture (IUPA) der Université Cheik Anta Diop in Dakar im Senegal, eine Tauchausbildung, um in ihr Wissen im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes „einzutauchen“. Das Problem dabei: weder sie selbst noch ihre Universität haben das Geld, um diesen Traum zu verwirklichen.

Deshalb haben Professor Malick Diouf, Nathalie Cadot, Patin des Projektes, sowie Ecofund das IUPA-Tauchprojekt ins Leben gerufen. Zunächst wird unter den fünfzehn Masterstudenten des IUPA an der Universität Cheik Anta Diop ein Team aus drei Studenten ausgewählt. Da es sich um ein Pilotprojekt handelt, sollen in diesem Auswahlprozess diejenigen Studenten gefunden werden, welche die besten Voraussetzungen für das Tauchen und die größte Motivation mitbringen, als Schützer der maritimen Ökosysteme Westafrikas zu grünen Champions aufzusteigen.

Diese drei Studentinnen und Studenten werden ihre Ausbildung um ihre neuen Fähigkeiten erweitern, insbesondere durch ihr Praktikum im zweiten Masterjahr und durch die Veröffentlichung von Artikeln und Exposés.

Ihr könnt ihnen dabei helfen, sich auf ihre Zukunft als Forscher und Meeresschützer vorzubereiten, und ihnen darüber hinaus eine einmalige Erfahrung ermöglichen, die für einige unter ihnen auch eine große physische Herausforderung bedeutet! Sie werden mit uns ihre Eindrücke und Emotionen aus ihrem Tauchkurs teilen und uns auf ihre Entdeckungsreise zu den Meeresgründen des Senegals mitnehmen.

Mit einer Säuberung der Bucht von N’gor von ihrem Unterwassermüll wird die Ausbildung dann am Weltmeerestag am 8. Juni gebührend abgeschlossen. Somit bekommen die Studenten ihre erste Gelegenheit, sich als aktive Schützer der Ozeane zu präsentieren. Viele andere Gelegenheiten werden folgen!

Das Ziel des Pilotprojektes ist es, aus dieser ersten Tauchausbildung einen vollen Erfolg zu machen, damit der Tauchkurs ein fester Bestandteil des Masterkurses wird und weitere Studierende davon profitieren können.

Wozu wir deine Spende brauchen?

Mit Eurer Spende finanziert Ihr für drei Studenten jeweils ein Stipendium für den Tauchkurs. Wie oben beschrieben, wurden unter den fünfzehn Studenten des Masterkurses diejenigen ausgewählt, welche den ersten Tauchgang (die „Taufe“) erfolgreich absolviert und uns durch ihre Motivation und ihre Zukunftspläne am meisten überzeugt haben. Jedes Stipendium erlaubt es uns, eine Ausbildung zum PADI Open Water Diver (neun Praxis- und Theoriekurse) sowie drei Entdeckungstauchgänge zu finanzieren. Die Ausbildung im PADI-System ist weltweit anerkannt und in den meisten Tauchzentren gültig.

Die drei ausgewählten Studentinnen und Studenten leisten einen Eigenbeitrag von jeweils 15 % der Ausbildungskosten und finanzieren darüber hinaus ihre Transportkosten zum Tauchclub, der sich in N’gor befindet.

Der Barracuda Tauchclub in Dakar unterstützt die Tauchausbildung, indem er 25 % der Kosten der Tauchtaufe und 15 % der Ausbildungskosten übernimmt sowie jedem Studenten ein AQUALUNG-Tauchkit mit Tauchflossen, Tauchmasken und Schnorcheln gratis zur Verfügung stellt.

Das IUPA übernimmt die Kosten seiner Lehrkräfte für die wissenschaftliche Begleitung der Tauchausbildung insbesondere bei der Beobachtung und Auswertung der Meeres¬ökosysteme während der Tauchgänge.

Die Anwendung des theoretischen Wissens soll dank der Tauchausbildung sofort erfolgen: Sobald die Studentinnen und Studenten das Wasser verlassen haben, werden sie ihre Stifte in die Hand nehmen und Euch diejenigen Pflanzen- und Tierarten vorstellen, die sie am meisten verwundert oder begeistert haben. Außerdem werden sie mit Euch ihre Ideen teilen, wie Westafrika und insbesondere der Senegal seine Meeresökosysteme am effektivsten schützen kann.

Ecopartner für Auf die Plätze ... lernt, taucht, schützt!

Professor Malick Diouf

Malick Diouf ist Professor, Forscher und Direktor des IUPA. Er ist Verfechter von angewandter Forschung und überzeugt von praxisnaher Ausbildung.

Er hilft lokalen Gemeinschaften, ihre natürlichen Ressourcen besser nutzen und schützen zu können. Er arbeitet zum Beispiel schon seit mehreren Jahren mit den Dorfbewohnern des Saloumdeltas (in Niodor, Fadiouth, Dionewar, Falia, Joal...) zusammen und unterstützt sie bei einer nachhaltigen Muschelnutzung.

Er liebt es, angewandte Forschung mit traditionellem Wissen zu vereinen, und setzt sich stark dafür ein, seinen Studierenden die Möglichkeit zu eröffnen, mit dem Gelernten zu experimentieren und es anzuwenden. Denn er ist überzeugt: „Die Bewirtschaftung und der Schutz der submarinen Ökosysteme lassen sich nicht nur aus Büchern oder in einem Klassenzimmer erlernen – sie er-leben sich!“

Letzte Meldung

21.02.2018 › Babacar's diving diary

Thanks to diving, I was able to discover marine habitats with high biodiversity. Among all the species, my attention was drawn to a snail largely found in warm waters and temperate regions of the world. Called Cymatium perthenopum, this latter has a very nice color, and though it is edible, it is still not well-known in Senegal. At first sight, I thought I was looking at a rock as its shell was covered by other sea organisms that helped it to blend into the decor. But once "unmasked", it was difficult to detach it from its base as it was well stuck to it!

Definition

Also known as Hairy Triton or hairy monoplex in reference to the hairy periostracum the most external part of the shell. The Cymatium perthenopum belongs to the Annelida family (i.e. worms). The shell is rather massive, brown in color with wide and thick edges. My catch measured 116.60 mm high and 59.70 mm wide. The perimeters are barely segmented and angular, with fine longitudinal stripes. The columella (edge of the shell near the opening) is folded. The labrum (outer edge opposite the columella) is jagged

The off-white body of the animal is spotted with large black dots giving it an aesthetic beauty. When it retreats into its shell, only its operculum is visible (a corneous or calcareous lid through which the snail can close its shell), thus protecting it from predators.

My specimen was caught 14 m deep on the rocks, but the species is found on all types of sea depths, from tidal current areas to areas as deep as 150 m.

The Triton snail is a nocturnal predator; it feeds mainly on bivalves, other gastropods and echinoderms (a group of marine animals like sea urchin and sea star etc.). If I get to master my diving skills, I may perhaps be lucky enough to observe them at night!

Fertilization occurs internally. The female lays eggs for 4 to 6 days in a capsule in the form of cup and incubates them for 16/18 days. Larval development lasts half a year (175 days).

Spread out over a broad geographic marine area, the Triton snail is not a threatened species but its biomass in Senegal remains unknown since the species is not yet well-observed. For this reason, funds must be made available to researchers for the study of the aquatic fauna of Senegal, to know it in order to follow up on its evolution. Much remains to be done in malacology (the study of molluscs) in Senegal for a better management of our environment. This is motivating for me!

Importance

The magnificent Triton of Naples’ shell is used as a decorative object, but the species is also edible and tasty especially when grilled and spiced up or simply boiled!

Some studies on this species have shown its use as a bio-indicator of marine pollution such as the pollution by tributyltin (TBT). This biocidal substance that contains tin comes primarily from anti-fouling paints applied on ships. They were totally banned from use in 2008 (fortunately, because they were too harmful to aquatic life).Did you know that

Commonly used in art as a decorative object, our gastropod appears on some paintings because of its beautiful shell. This species is considered in some regions as harmful due to its predatory activity in oyster parks. Its harvesting in the West African sub-region is not so significant.

17.02.2018 › Amadou's diving diary

Living along Senegal’s coastline, I eagerly awaited the harvesting season for these balls of spines with an exotic taste. During our initiation to diving, I was struck by the diversity of urchins in the Bay of Ngor in Dakar. In fact, it was my first time of seeing Diadematids, a species that is totally different from those we are accustomed to seeing. For this reason, I have chosen to share this wonderful discovery with the Ecofund community. However, I vividly remember how these beautiful "tiaras" were removed from hands (mine) and have not forgotten yet their painful spines!

Definition

Urchins are marine invertebrates, a species belonging to the Echinodermata family (such as sea stars and sea cucumbers). These small balls covered with spines are called "Saukhaure" in Wolof. We know the Echinometra lucenter species because we pick and roast them often right on the rocks bordering the sea. However, the species that I dissected in the laboratory was harvested from a depth of between 10 meters and 16 meters in the north of Ngor island, and this was only possible through practicing diving, and I am very proud of myself!

Lucenter Echinometra and Eucidaris tribuloides are the most common species and they are characterized by short spines which are thick for E. tribuloides and more or less thin for E. lucenter. Unlike these, diadems (Diadema africanum and antillarum) are the least known sea urchins in Senegal and they are characterized by their long and thin spines which can measure over 10 cm. Diadematidae derive their name from their beautiful shape and their preference for warm waters, one reason why they are mostly found in the eastern part of the Mediterranean where they are a protected species. They are also abundant in the shallow depths of the eastern Atlantic (for example in Senegal and Cape Verde).

They feed by scrapping and shredding plants lining the sea bed with the help of their mouth fitted with special jaws called "Aristotle lantern". The sexes are separated, and fertilization occurs externally through the simultaneous release of gametes into sea water. To the naked eye, the distinction between the male and female is impossible.

As for the spines which I personally tested, the shortest are filled with a non-potent venom for humans. However, broken spines are more difficult to pull out and can infect a wound.

Importance

Today, there are only 800 species of sea urchins identified worldwide at different sea depths. It is important to conserve sea urchins as they are used as an important “biological indicator” for man. In fact, the larvae of sea urchins may carry deformities due to pollution, which will prevent them from reproducing thus causing a decrease in the local population. In addition, researches on the genetic composition of urchins are being carried out for the treatment of cancer. The sea urchin is a perfect laboratory specimen as its cells multiply in less than two hours against 24 hours in humans and with 70% of its genome being similar to the human genome (i.e. all the genes carried by the chromosomes of a cell). Studies at the Roscoff Biology Station, France, have also helped to highlight the A1 peptide which helps in fighting leukemia.

Some species of sea urchins are edible as seafood. These edible ones are harvested by hand, using a hook or a simple knife. The edible parts are the five reproductive organs (gonads). To reach these organs, the mouth and the digestive apparatus are removed. In Senegal, they are eaten grilled on almost all the beaches and remain a flourishing business managed in general by Lebou women.

Additional information

The tests (or shells) of dead sea urchins have a spangled design, which can be clearly seen in some species, and mainly in irregular urchins with the design showing in the form of a flower. This has turned them into aesthetic objects, sought by certain collectors or used by some as decorative objects, ritual objects or amulets. They are also used in the decoration of tombs or religious monuments, portraying a large symbolic diversity based on the people

15.02.2018 › Fatou's diving diary

A humorist once wrote: "an oyster is a fish built like a nut," Pteria sp oyster, is something like that…

When I was five or six years old, I was picking sea shells on the shores of Dakar suburbs. I could never have imagined that there were living organisms inside these cockles.

It was after my diving ‘baptism’ that I had the opportunity to observe them in their habitat (scientifically called biotope). I have been fascinated by the way in which some bivalves (aquatic molluscs with two distinct separated parts that are more or less symmetrical), attach to rocks. As a natural base to many other living things (Cnidaria such as sea anemones, jellyfish, corals or other molluscs and algae), bivalves have developed a system of camouflage to escape their predators such as some boring gastropods (Netica SP) and non-borers (murex). This is what prompted me to choose the Pteria SP oyster, a species of the pearl oyster family. With its hiding system, the harvesting deserves special attention because for the uninitiated, it may go unnoticed…Diving has thus helped me tremendously in my scientific exercise!

Defiition

The Pteria SP oyster is closely related to the pearl oyster of the family of Pteridae and the Pteria genus. Its shell which can measure from 35 mm to 280 mm, is thin, fragile and can have a very variable form: oval, circular and sometimes very elongated on one of its sides, calling to mind the wings of a bird. Its hinge, the part connecting the two valves on the thickest side of the shell, has no tooth. The animal has no foot but a very developed adductor muscle running along the central part of the shell. It is this muscle that ensures the closure of the shell

The specimens collected were found at a depth of 12 m. They attach to rocks through a secreted bundle composed of a set of filaments or threads called byssal.

These bivalves are biofilters. They feed on food particles (organic and inorganic) suspended in the water.

The sexes are separated, but we have no precise information on their reproduction.

Apart from the pearl oyster, edible Pteridae are not, as far as is known, highly harvested.

Importance

Although many bivalves in this family can secrete pearls, the Pteria is not used for this purpose. Long confused with the oyster, and later with Saint James shell, the Pteria is mainly sold by women on Soumbédioune beach in Dakar. The species is eaten fresh and grilled. Sellers even attribute aphrodisiac powers to these shells!

Did you know that

In Senegal, the empty shells of this species are used for decorative purposes. However, some ethnic groups such as the Sérère use them for building "Bankos" (huts built with clay). Indeed, after burning the shells, the calcareous shells are used as a binder for the whitewash.

30.11.2017 › 15th project funded and accompanied by Ecofund

We are happy to announce the successful implementation of the project “On your marks… study, dive, protect!” This is the 15th project funded and accompanied by Ecofund.

The project was born thanks to the initiative of Professor Malick Diouf at the University of Dakar, his Msc. students in 'Aquatic Eco-systems Management' and thanks to the collaboration with the Barracuda Club Dakar.

Many thanks to all of you for your support and donations! Special thanks to the Rotary Club Dakar for filling the budget gap!

The project’s results are best resumed by the passionate scientific articles written by our three students freshly graduated at PADI Open Water Divers. The articles translate best how the opportunity of diving, and thus observing the natural underwater environment for the first time, has positively impacted their studies. During the diving sessions the students collected few specimen for further observation and study at the University of Dakar.

We invite you to visit our “Green News > Ecoblog” page and to read the articles on three specimen, of which you would not imagine the virtues and the utility for our oceans and our lives.

At the end of our journey “On your marks… study, dive, protect!”, it is also time to sit back and make an evaluation - we learned at least two lessons:

- The more a scientist “dives” into the natural environment, the more he gains know-how and proficiency. This seems obvious, however this is not the common practice during the 'Aquatic Eco-systems Management' studies at the Cheik Anta Diop University in Dakar. This first underwater diving training has been a pilot project and – to our opinion - a real success. We hope Professor Malick Diouf can capitalize on this success, so underwater diving training becomes part of the university syllabus to help students become future champions in the protection of marine ecosystems in West Africa.

- To be a scientist working on preserving our ecosystems is good, being a passionate scientist and communicating your passion is even better. This helps a lot to spread the knowledge and sensitize people to adopt an eco-responsible behavior.

During project implementation, our three students have demonstrated their eco-responsible behavior by participating actively in cleaning-up sessions of the N’Gor bay in Dakar in Senegal and its underwater environment. The cleaning-up sessions were organized by Julie, Nathalie and Franck from the Barracuda Club Dakar. For example, on the World Oceans Day, in less than 2 hours, 1 ton of garbage was collected, of which 650 kg on the beach and 300 kg under water!!! This is good but how much waste lies still on the bottom of our oceans? More than ever, our three champions will need to develop ideas on the ways how West Africa can strengthen protection of its oceans.

During project implementation we also encouraged the students to demonstrate their ownership by co-funding this pilot project by their university mates. Crowdfunding is not yet an established practice in West Africa since contributing 10.000 Francs CFA (15 euros) represents a lot of money for a student in Senegal. Therefore, the fact that they succeeded to raise among their university mates 300 Euros is an encouraging step. Though it is a partial amount (17% of the project budget), the symbol is important since the University and the students want the underwater diving training to become an integrated part of the master course in 'Aquatic Eco-systems Management’. Alike Fatou, Amadou and Babacar, the students will need to merit the diving training and also prove its utility for science and the protection of oceans.

Last but not least, we want to congratulate Fatou, Amadou and Babacar and wish them all the best for their future as professionals in protecting the aquatic environment.

Enjoy their articles, which may give you the stimulus to explore the underwater world in West Africa.

16.09.2017 › International Coastal Clean-up

When?

Thursday 16 September, from 9 a.m. till 12 a.m.

Where?

Join us at the N’Gor beach in front of the Black&White club in Dakar, Senegal

Divers please call 77 099 97 66 (Senegal)

What?

Not talking – acting!

Clean-up of the beach and the underwater environment of the N’Gor bay.

If you cannot join us, with Ecofund, Barracuda Club and the IUPA you have still the opportunity to act in a concrete manner by supporting our champions Fatou, Amadou and Babacar by making donation to the project “On your marks… study, dive, protect!

11.06.2017 › Our oceans, our future!

The “World Oceans Day” started with a Conference at the University Fishing and Aquaculture Institute IUPA in Dakar, Senegal with a participation of more than hundred students and of course our 3 champions, Fatou, Amadou and Babacar.

Fatou, Amadou and Babacar, made a surprise: they performed a sketch they have written in order to alarm their fellow students about the negative impact of plastic pollution, see the video below.

Thus, the conference was a very reach exchange of expertise and experiences on the pollution of our oceans and in particular on how to reduce or - even better – avoid it !

From talking to acting:

From 4 p.m. divers from the Barracuda Club Dakar, our 3 champions, Senegalese fire fighters, and surfers, BRI action and JFD, the N'Gor Island Surfcamp and "l'Amicale des amis de la baie de N'Gor", all together fifty volunteers came to the N’Gor bay in Dakar, Senegal, to clean-up of its beach and its underwater environment.

In less than 2 hours, 1 ton of garbage was collected, of which 300 kg on the beach and 650 kg under water !!!

It was a perfect opportunity for our 3 champions from the IUPA, just certified divers, to participate in the cleaning and thus to demonstrate their engagement for the protection of our oceans.

We are very curious to learn about the species they discovered, which intrigued or amazed them in particular during the diving training, as well as share their ideas on the ways which West Africa can strengthen protection of its oceans.

05.06.2017 › World Oceans Day

When?

Thursday 8 June

Where?

From 9 a.m. join us for the conference at the University Fishing and Aquaculture Institute IUPA in Dakar, Senegal

From 4 p.m. join us at the Barracuda Club Dakar N’Gor for clean-up of the beach and the underwater environment of the N’Gor bay in Dakar, Senegal

What?

Not talking – acting!

If you cannot join us, with Ecofund, Barracuda Club and the IUPA you have the opportunity to celebrate the World Oceans Day in a concrete manner by supporting our champions Fatou, Amadou and Babacar by making donation to the project “On your marks… study, dive, protect!

Your personal Happy World Oceans Day Gift!

27.05.2017 › Und hier sind Fatou, Amadou und Babacar unsere künftigen grünen Champions !

Wir freuen uns, Euch das Team der drei ausgewählten Studenten des Masters für „Meeresbiologie und Meeresökonomie“ am Institut Universitaire de Pêche et d’Aquaculture (IUPA) der Universität Cheik Anta Diop in Dakar im Senegal vorzustellen: Fatou, Amadou und Babacar wurden unter 15 Kommilitonen ausgewählt, da sie die besten Voraussetzungen für das Tauchen und die größte Motivation mitbringen, als Schützer der maritimen Ökosysteme Westafrikas zu grünen Champions aufzusteigen.

FATOU KINE GUEYE

Ich bin 25 Jahre alt und ich bin eine der wenigen Frauen des Studiengangs. Wenn ihr bedenkt, dass ich keine große Schwimmerin bin, dann versteht Ihr, warum ich sehr motiviert sein muss, diese Tauchausbildung zu machen: sie ist eine große physische Herausforderung für mich ist. :-)

Nach meinem Abitur in Geo- und Biologiewissenschaften habe ich den eingeschlagenen Bildungsweg weiterverfolgt und mich nach meinem Bachelorstudium an der Universität Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar für den Master der IUPA entschieden und dies aus zwei Gründen: Ich war schon immer eine begeisterte Entdeckerin, vor allem im Wasser, und ich wollte mich auf den Umweltschutz, genauer gesagt auf Meeresschutzgebiete spezialisieren. Darüber hinaus hat man mir das IUPA Institut wärmstens empfohlen.

Meine Eindrücke im Wasser?

Während des ersten Tauchgangs hatte ich eine einzigartige Erfahrung. Es war genauso wie in den Reportagen! Ich war von der Vielfalt der Formen und Farben der Algen sehr beeindruckt, sowie von der Art wie sie sich an den Felsen festkrallen. Außerdem habe ich eine sehr farbenfrohe Spezies entdeckt, der mir sehr gefallen hat: ein Nacktkiemer! (siehe Foto)

Alles in allem war es eine entdeckungsreiche Erfahrung!

Ich kann die nächsten Tauchgänge kaum abwarten. Ich finde die Tauchausbildung sehr motivierend für mein Studium und ich merke, dass ich im Vergleich zu den anderen Studenten mein Studienfach "leben" kann. Deswegen möchte ich noch einmal die Gelegenheit nutzen, Euch allen für Eure Unterstützung zu danken.

AMADOU SENE

Ich bin jung (26 Jahre alt), liebe mein Studium, und ich denke, ich wurde von der Jury für dieses Projekt ausgewählt, weil ich für diese Tauchausbildung einer der Motiviertesten der Gruppe bin!

Schon in meinem Bachelorstudium faszinierten mich die Fächer der Naturwissenschaften, darunter auch die Ökologie. Wir lernten viel über Beziehungen zwischen den verschiedenen Elementen unserer Natur und wie wichtig es ist, diese gut zu verstehen. Als ich dann in der Tierkunde hörte, dass der Großteil unserer Lebewesen im Wasser lebt, hat es bei mir geklickt und so habe ich meine weitere Ausbildung auf die Ökologie der Meeressysteme fokussiert. Ich möchte später als Experte in diesem Bereich sehr nützlich werden, da immer noch viele Informationen über die zahlreichen Arten und über den Zustand unserer Küsten fehlen. Das ist für den Senegal eine echte Herausforderung: eine erfolgreiche Fischereibewirtschaftung hängt von der Gesundheit unserer Meere ab, und deswegen müssen wir die Zerstörung unserer Meeresumwelt verhindern. "

Was hast du während des ersten Tauchgangs unter dem Wasser empfunden ?

Ich hatte unter Wasser eine einzigartige Erfahrung. Meine große anfängliche Angst ist schnell verflogen als wir auf verschiedene Arten gestoßen sind, die wir bislang nur aus unseren Büchern kannten, wie zum Beispiel Seeamonen und Kugelfische. Der Kugelfisch war sogar das Thema meiner Forschungsarbeit! Ich war außerdem beeindruckt von der nahezu magischen Fähigkeit, unter Wasser atmen zu können!

Für all das, und es ist erst der Anfang, danke ich für die Unterstützung, die Ihr uns zukommen lasst. Sie ist von enormer Bedeutung für den erfolgreichen Abschluss unserer Forschungsprojekte.

BABACAR SANE

Ich wurde am 10. Februar 1992 in einem Dorf im Departement Podor geboren. Dort habe ich auch Schwimmen gelernt.

Meeresökologie war schon immer mein Traum: ich habe Lust, mitzuhelfen die marinen Ökosysteme zu schützen. Deshalb erlaubt mir der Studiengang, den ich am IUPA gewählt habe, meine bisherigen wissenschaftlichen Kenntnisse zu vertiefen. Zum Beispiel möchte ich mehr über die Auswirkungen der Verschmutzung der Meere erfahren, die meiner Meinung nach besser geschützt werden müssten, nicht zuletzt vor dem Hintergrund ihrer Bedeutung für die senegalesische Fischerei, aber auch für unser eigenes Wohlergehen. Als Kind des Flusses von Podor will ich gegen die Schädigung der aquatischen Umwelt ankämpfen.

Und was waren deine ersten Eindrücke unter Wasser?

Als ich während der Tauchtaufe zum ersten Mal in das Wasser gestiegen bin, war das einzigartig und wunderschön. Ich sah zum ersten Mal einen richtigen Fischschwarm und verwurzelte Algen und viele andere schöne Dinge! Normalerweise sehe ich das nur auf Videos. Ich dachte mir "Das ist genial! Ich atme unter Wasser!" Das ist eine Erfahrung, die ich nicht so schnell vergessen werde.

Und dafür möchte ich Euch allen herzlichst danken !